Much of the Christian art of the catacombs pre-dates the Council of Nicea in 325 AD. But what is the nature of this art? What was it used for?

In this post, I will examine one kind of image in the catacombs—portraits of the deceased Christian in the form of an orant—and argue that it was intended to be used ritually by Christians. Some orants facilitated the veneration of images of Christ, while others were themselves venerated. This way of understanding these images is supported by mainstream historians of art and early Christianity.

This will be the first archeology-based offshoot from my ongoing series of posts responding to Dr. Gavin Ortlund’s arguments that veneration of images is a late development in Christian practice that only became mainstream after the Council of Nicea.

Establishing How Art Was Used

In a previous post, I noted that the mere existence of early Christian art does not show that such art was venerated. Not all art has the same use, and just because someone has paintings in his or her house, it doesn’t mean he or she venerates said paintings. Your aunt probably (hopefully) does not bow her head and light a candle in front of her Thomas Kinkade.

However, inquiry about image veneration does not end here. Because some images are given a ritual, cultic use, it is possible to show that a given image was venerated. This can be done even in the absence of written instructions about the use of an image or accounts of how people interacted with them. To argue for how an image was used, we can undertake an examination of the formal qualities of the image (shape, directionality, etc.), compare it to other images whose usage we know, and adduce considerations of context as well (where the image is located, who likely composed it, other images around it, etc.).

These arguments will not be conclusive; but neither are arguments about how to interpret a text. In many cases, archeologists and historians can conclude with high probability and considerable clarity how an object was used. It will not be a complete explanation. But to bring up the comparison to text again, a complete explanation of what an author meant by something is not necessary to draw some very firm conclusions about what he or she meant.

Scholars of early Christian art are increasingly drawn to the concept of “ritual-centered visuality”: early Christian images were made to be interacted with. Aspects of this view can be found in mainstream scholars such as as Michael Peppard, Robin Jenson, Beat Brenck, James Hadley, and Norbert Zimmermann, who each acknowledge that some early Christian art appears “open-ended”. It is meant to be interacted with by the viewer, not just looked at.

For example, Michael Peppard in his paper “Early Christian Art and Ritual”1 notes the existence of an early Christian altar with a loaf of bread painted on all four sides. The number of loaves reminds one of Jesus’ feeding of the 5000 using 5 loaves of bread, which early Christians connected to the Eucharist. But where is the fifth loaf? The answer is that the multi-part image itself is incomplete apart from the interaction of a priest or bishop, offering up the Eucharist, placing the fifth loaf on the altar. The image is indeed open-ended, incomplete apart from the ritual interaction of a person.

What Is An Orant?

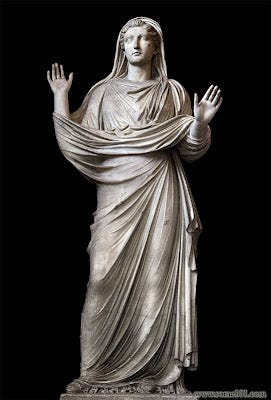

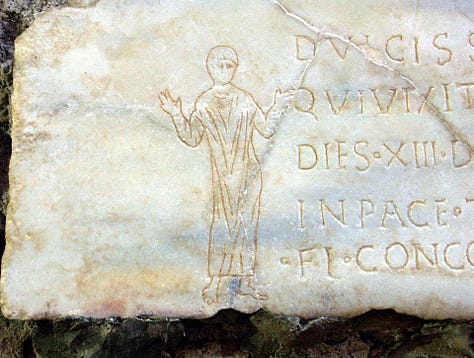

An orant is a common figure in ancient mediterranean and ancient near eastern art. In Roman contexts, the orant is usually presented as a veiled woman with hands outstretched upwards. This stance is one of prayer, and the orant is considered to be primarily an image of piety. Roman piety was connected with the civic cult, and the practice of worshipping idols and honoring the emperor. The orans stance was a typical prayer stance of ancient Roman people who engaged in these cultic activities. Arms outstretched in prayer (often with elbows remaining close to one’s body) suggest supplication, request, devotion, and a connection to a patron from whom generosity is expected (or at least hoped for). There is a deep unity between this physical stance of prayer and certain inner attitudes which modern people would more directly identify as “spiritual”. But of course this kind of sharp distinction between physical ritual action and inner spiritual attitude is simplistic and modern, and Roman piety was very external. Orants show up as statues, on gravestones, and in a number of other places.

The fact that orant images in the ancient mediterranean and ancient near east had a ritual use is well-evidenced and not controversial. DiYanni Benton gives the following examples:

"...it appears that Sumerian people might have a statue carved to represent themselves and do their worshipping for them—in their place, as a stand in. An inscription on one such statue translates, 'It offers prayers.' Another inscription says, 'Statue, say unto my king (god)..."2

This supplicatory role of art shows that orants were not mere decorations. The act of depicting an orant figure is deeply connected with the activity of prayer itself.

The Role Of Orant Images In Evoking Image Veneration

When we turn to the early Church, we can immediately note that Christians adopted this prayer stance as well. Saint Paul writes:

[1Ti 2:8 ESV] 8 I desire then that in every place the men should pray, lifting holy hands without anger or quarreling

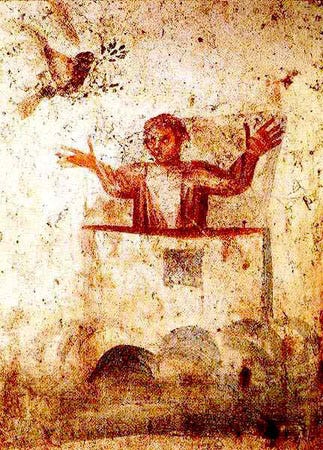

Early Christians included in their spaces painted images of persons engaged in prayer, exemplifying the orans stance. In early Christian art, we can note three typical kinds of orant figures: orants that seem like more generic images of piety (often depicted without a clear face), biblical characters requesting salvation (like Noah in the ark), and portrait orants who appear as representations of actual historical persons:

Norbert Zimmerman, one of the foremost contemporary researchers of the catacombs, dates many of the orant images prior to 300AD. He regards the salvation-orants which portray scriptural events as older, but notes that portrait-orants emerge prior to the end of the third century:

“Imbedded in this clear repertory of mostly biblical scenes, at the very end of the third century,a further new, most important image, widespread in the traditional art, was added to this meaningful content: the portrait of the deceased. Even though it appears relatively late, it soon became the statistically most represented single motif of catacomb art…”3

While not every image in the catacombs is pre-Nicene, at least some of the portrait-orants are this early; this is also the judgment of Robin Jenson.4 This makes the question of whether they were connected to practices of image veneration particularly important.

There are several good reasons to think that portrait-orants were used in a ritual manner. Arguments can be made on the grounds of an orant’s formal qualities, by comparison with other images whose use is known, and by considering the context in which the image is situated.

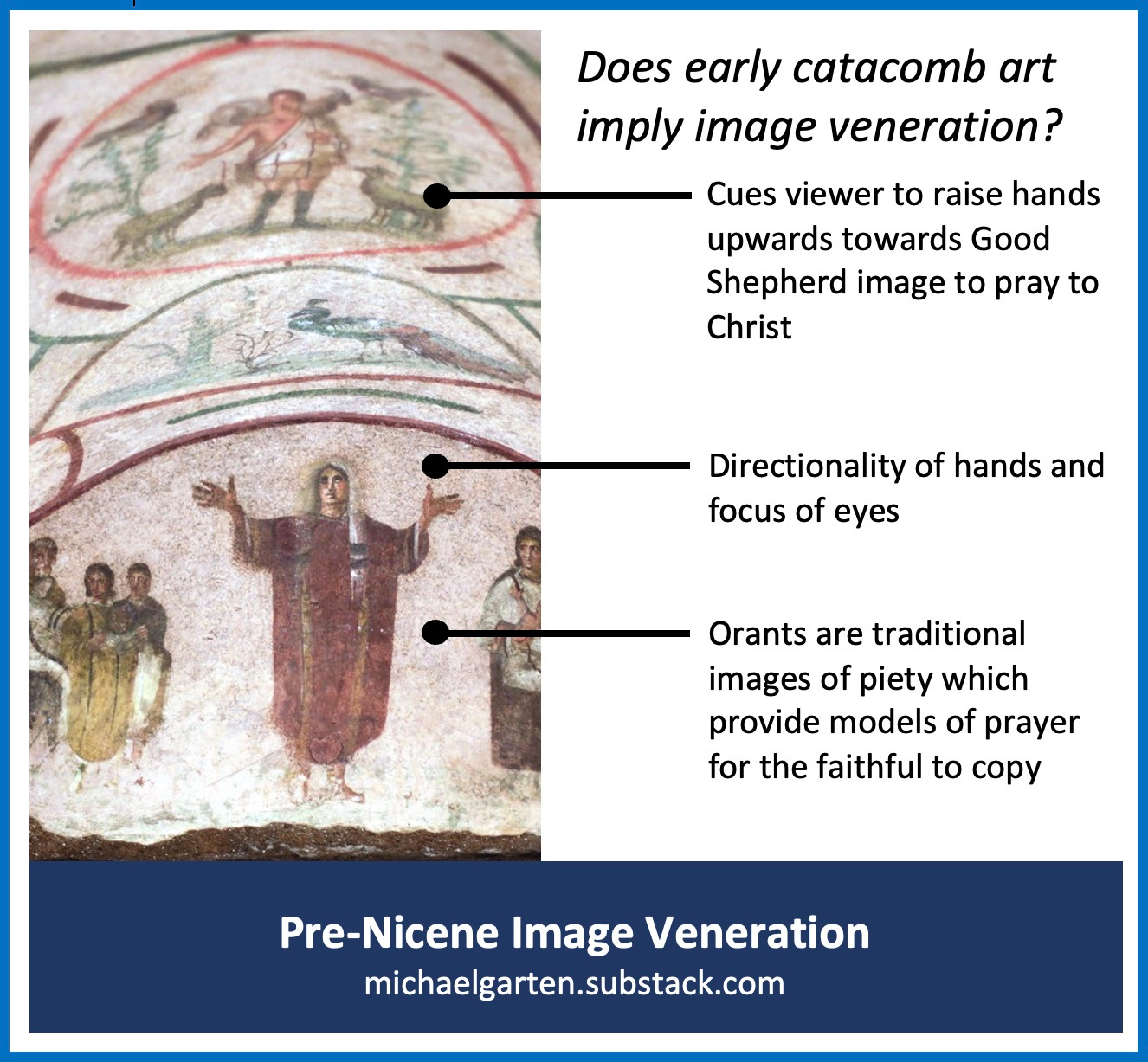

The orant image called the “Donna Velata” (veiled lady) in the Catacomb of Priscilla plausibly depicts the person buried there. This image shows a directionality which relates to another image in its context. The gaze of the orant and her hands point upward. As an image of piety, she is meant to be emulated. The attention of the pious Christian is thereby draw upwards, with eyes and hands pointed towards the ceiling also.

The Christian’s focus coalesces on an image of Christ as the Good Shepherd above. Gathered around Him also are adoring sheep or goats, representing Christians who are recipients of salvation. The sheep around the shepherd further gather one’s attention, directing prayer and love to the Christ who is shown in the highest place. This framing is met by the image of the Good Shepherd, a sign of divine presence in the underworld. Thus, the Christian’s attention ascends through prayer and piety (through the orant) into an attitude of total focus and reliance (through the sheep or goats), and finally to Christ Himself (through the image of the Good Shepherd).

When we take into account the formal qualities of the orant (directionality of eyes, hands), its relationship to other images (Roman orants as presentations of piety, and the ritual use of Sumerian orants), and the context in which the image is situated (beneath the Good Shepherd who is also surrounded by the gaze of the sheep) we have strong reason to conclude that this portrait-orant is supposed to serve a cueing function. It was meant to elicit in the pious Christian an identical posture of outstretched hands towards the Good Shepherd as imaged above, and the corresponding inner attitude of prayer. In other words, the orant was meant to evoke veneration of the Good Shepherd image above.

Ritual Role Of The Orant According To Scholarship

This interpretation is not only plausible on the grounds of the above-listed evidences; variations of this view are widely-accepted in scholarship.

Michael Peppard describes the ritual use of one particular orant image in the Coemeterium Maius along the Via Nomentana. This orant is identified as the buried Christian, and serves a cueing function. She is part of an “open-ended” image, referencing Christ’s parable of the 10 virgins, but displaying five foolish and only four wise virgins. Where is the remaining wise virgin? The Christian buried in this space became the final “piece” of this image, and was represented as the orant in the center, praying upwards towards the Good Shepherd. However, the image was not just “open-ended” for the buried Christian—it was also completed by visitors to her tomb. Peppard remarks:

“[in] the catacomb example…through the rituals of prayer and the refrigerium, the visitors to these graves joined with the body before them in order to move the orant on the wall one step closer to her banquet. The incomplete picture of the incomplete narrative was intended as such because the rituals performed in this space helped to complete it.”

This analysis does not explicitly state that the image facilitated a stance of prayer towards Christ through the image of the Good Shepherd above it. But the cuing of “rituals of prayer” which “joined with” the person who is buried to move her closer to the heavenly banquet would involve directionality. Part of the way the orant cues prayer is by directing people beyond herself, towards the Good Shepherd as a manifestation of the Christ who can answer those prayers and fulfill the request for participation in His heavenly table. Her image therefore imparts a directionality of the “rituals of prayer” which would entail the believer’s own orans stance (from Peppard’s emphasis on “jointed with”). This stance would involve interaction with the image of the Good Shepherd, with prayers passing through it to supplicate Him.

Robin Jenson’s interpretation of the orant figures coheres with and builds on Peppard’s. She focuses on two female orant figures in the Catacombs. The first is from the Catacomb of Priscilla:

“Often referred to as ‘Donna Velata’ (the veiled lady), this orant is garbed in a dark red dalmatic with two vertical bands and a while veil with dark stripes that reaches nearly to her waist (Figure 34.3). Vividly rendered, her hands reach up as if animated and she casts her eyes upwards and to her right as if in appeal to a heavenly being. Her relatively large size and central placement make her a commanding presence in this small chamber; she is the first image that catches the visitor’s eye, perhaps meant to model the attitude they should affect as they entered her space.”5

The idea of cueing is clear here, not only in Jenson’s comment about how the orant models the attitude which a visitor should have, but also in the language of “commanding presence”, “catches eye” and “her space.” The orant’s attitude (which is meant to be modeled) is manifested and imparted to visitors in how “her hands reach up” and “she casts her eyes upward.” While Dr. Jenson does not specifically identify the Good Shepherd as the focal point of this orant’s devotion (preferring for some reason the vague language of “a heavenly being”), this is the most obvious candidate image to clarify Who is being prayed to.

Her second reference is to the Catacomb of San Gennaro, and here Jenson focuses on a woman named Cerula who is depicted as an orant similar to the Donna Velata:

“Above her head is a tau-rho figure flanked by an alpha and omega. To her right and left are books, identified by titles as the New Testament gospels. Her visage, as in the Priscilla catacomb, seems to portray a particular woman, possibly the individual buried in this cubiculum. Because she remains in perpetual prayer, her image prompts the faithful who enter to join her and, perhaps, to be attentive to the beloved scripture stories of God’s reliable rescue.”6

Jenson’s description of the image of Cerula as being designed to “prompt” the faithful to “join her” in prayer is another instance of scholarly support for the interpretation of the catacomb art as having a cueing function, and imparting ritual participation. The tau-rho figure above the depiction of Cerula is a staurogram, one of the earliest ways of visually depicting the crucified Christ. This indicates the ultimate directionality of her prayer: towards the Son of God who died to save her. This orant figure was painted (at least) for a ritual function of bringing faithful visitors of her tomb to pray to Christ.

Were Portrait-Orants Ever Venerated?

However, it is possible that some portrait-orant images were intended for veneration themselves. This goes beyond the cueing function of directing a stance of prayer upwards towards the Good Shepherd or staurogram images, as we saw in the Coemeterium Maius and Catacomb of Priscilla. It would instead involve a ritual interaction with the painted image of the orant-saint.

Zimmerman distinguishes different kinds of orant figures based on their directionality, and comments on their cultic use. He begins by stating an interpretation of the catacomb art that is somewhat similar to Peppard and Jenson’s about the ritual use of images, but builds on it in important ways as he considers the directionality of orant-portraits:

“These portraits send messages of the status of the depicted in society and identify membership in a group or class in life or hopefully in the afterlife. Some of them become proper prayers when the deceased is shown making eye contact with Christ, bringing personally the wish for salvation before his face. A good example is in arcosolium of the Domitilla catacomb: Christ appears as the Good Shepherd, and the deceased as part of his flock, a female orant at his right side looking directly at him, as if praying personally for her salvation.”7

Zimmerman’s interpretation is that the very composition of some orant images is a prayer. By depicting the deceased as an orant at the right hand of Christ, those who composed the painting were effectively saying “we who are living join in her prayer to You”. There is continuity here with Peppard’s idea that some of the images of orants are meant to serve as requests that the faithful pray for the soul of the deceased person specifically.

Zimmerman continues, noting the fact that other orant-portraits have a different directionality:

“However, in the majority of portraits the individual depicted looks straight ahead out of the image, as if to make eye contact with the viewer. And this seems to be their function in most cases: to communicate directly with the viewer in the moments of cultic commemoration and contemplation. At least two times a year the family held a meal and visited the tomb, during the rosalia (feast of roses), the commemoration day for the deceased, and the day of passing away, regarded by Christians as the deceased’s birthday to the eternal life.”8

The “cultic commemoration” by visiting, visually focusing on, and engaging spiritually with the departed Christian by means of a portrait is a form of image veneration. On Zimmerman’s interpretation, the orant-portrait becomes a means to do this because of what it is capable of doing as a ritual object: these portrait orants “communicate directly with the viewer” because they are composed “as if to make eye contact with the viewer.” This is clearly a cultic use of images, and the modes of physical interaction mentioned above (visitation, beholding) acknowledge and honor the image in question as one spiritually interacts with the person depicted.

Because this involves the ritual interaction with a Christian who has passed on from this life, we can see this practice as connecting to prayers to saints. Zimmerman’s own interpretation does not necessarily identify the deceased as an intercessor, but rather as one for whom intercession is being made by the living. However, it is not too far-fetched to see how this can become prayer to a saint. Early Christian sources acknowledge the intercessory role of the deceased, and if someone lived with a certain level of holiness (especially martyrs) it would automatically be more natural to ask for their prayers when ritually engaging with that person through his or her portrait. This question of the degree of holiness of a person may also change how we interpret orants who are facing Christ (like the one Zimmerman mentions in the arcosolium of the Domitilla catacomb). If painting the orant could be a way of joining in prayer for him or her, it is much more reasonable to think that the portrait of someone who has received abundant holiness (martyrs, confessors, etc.) would be a means of requesting prayer from that holy person.

Conclusion

Many portrait-orant images in the catacombs were used ritually. When we consider their directionality, relationship to other images whose usage was known, and position among other images, we can understand the purpose of some portrait-orants. They were meant to evoke a visiting believer’s prayer to Christ through his or her own orans stance directed to the Good Shepherd image above. Other portrait-orant images that gaze towards the Christian viewer should be interpreted as meant to evoke spiritual interaction with the depicted deceased Christian through visiting, acknowledging, and focusing on the image.

Both ways of interacting with portrait-orants are forms of image veneration: praying to Christ through hands outstretched to an image of Him, or interacting spiritually with a departed saint by visiting, acknowledging, and focusing on the saint’s image. We are on firm grounds in saying that these images (several of which are pre-Nicene) are evidence that early Christians had practices of image veneration.

Peppard, Michael “ Routledge Companion to Early Christian Art

Benton, DiYanni, J. R, R (2008). Arts and Culture: An Introduction to the Humanities. Upper Saddle, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 9.

Zimmerman, 26 in

Jenson, Robin “Ritual and Early Christian Art” (2018) in The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Ritual, ed. Risto Uro. Oxford Univeristy Press. p. 589

Jenson, p. 591-592

Jenson, p. 593

Zimmerman, p. 27

Zimmerman, p. 28-29