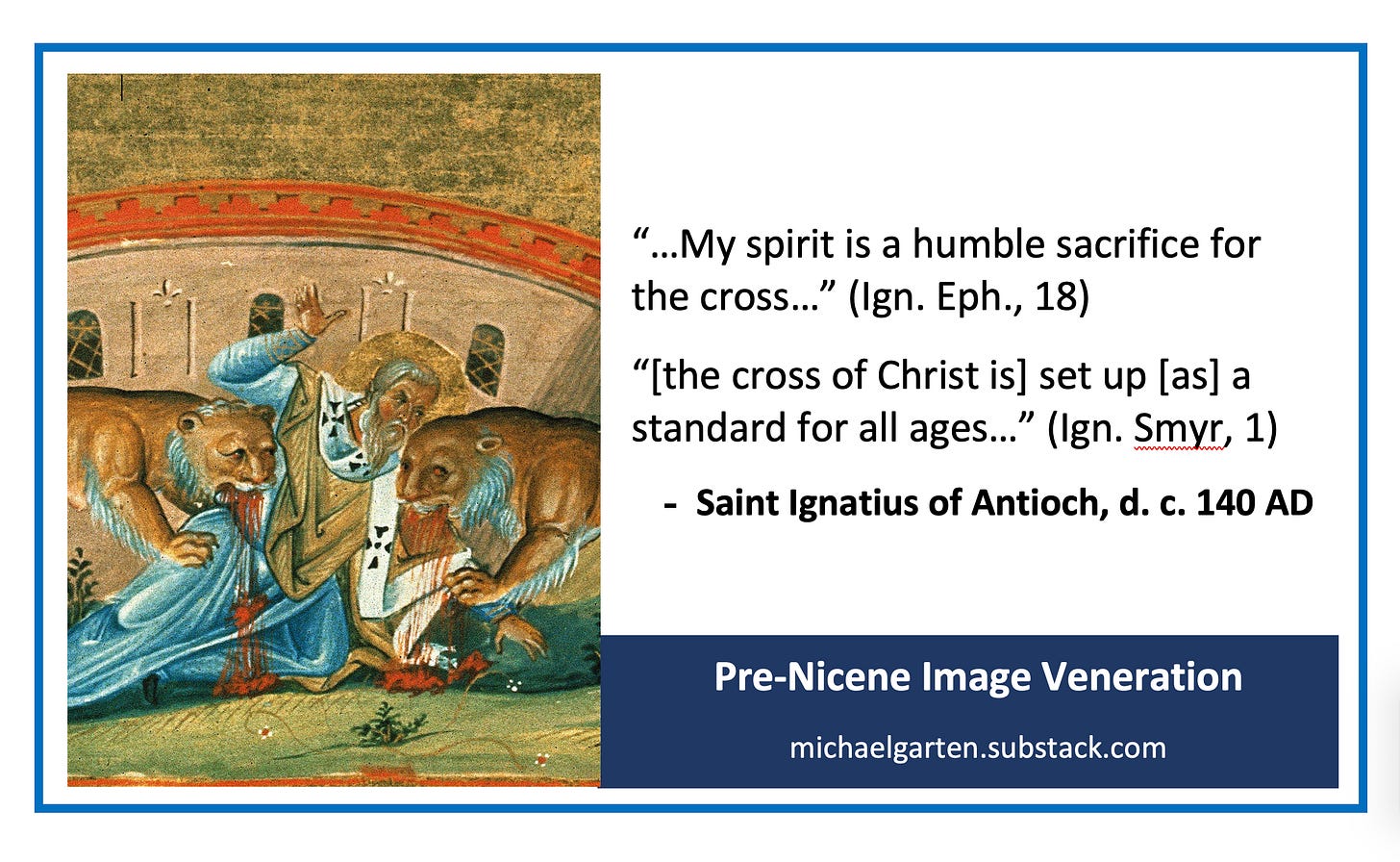

One of the earliest Christian writers after the New Testament is Saint Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch. Known for his many letters (so early that they still carry the flavor of a Pauline or General Epistle), this Saint is famous for his faithfulness to Christ in the face of martyrdom. Because he is an extremely early Saint (who died at latest around 140AD) who knew and learned from the Apostles and was charged with preserving their teachings, it is unlikely (even on a merely historical level) that his understanding of Christian teaching would be a post-Apostolic corruption.

Because he is such an early witness, it is very important that Saint Ignatius has a highly-developed theology of the cross, and practices the veneration of it. This is attested in several passages in his authentic letters.

The Cross as Manifestation, Sign, and Trophy of Christ’s Death

The teaching of St. Ignatius on the cross connects to his endless pursuit of Christ in the face of suffering. In a variety of ways, he explains the significance of the cross in manner which distinguishes it from the death of Jesus itself. This is not to say he regards the passion of Christ and the physical cross as separate; obviously the cross is an inseparable manifestation, sign, and trophy of Jesus’ death. And yet, in the passages below, it is clear that the cross is not strictly identical to it.

Instrument of salvation: in his epistle to the Ephesians, section IX, Saint Ignatius says the cross is the mechanism (μηχανῆς) by which humans are drawn to heaven and united to God, and the means by which God calls us (Trallians, XI). This treats the cross as having an inherent efficacy (though obviously this power is only present in it because of Jesus’ death upon it).

Tree of life: the Saint also speaks of the cross as a tree, and says that any people who are planted by God the Father will "appear as branches of the cross, and their fruit would be incorruptible." (Letter to the Trallians, XI) This is an identification of the cross with the tree of life, possibly the earliest clear identification of this kind in Christian writings.

In all of these sections, St. Ignatius speaks of the cross as distinct from Christ Himself, but an inseparable manifestation of His passion. It is treated as an object that extends Christ's power into the world. Given Saint Ignatius’ statements about the power of Christ present in the cross, it is natural to predict that Saint Ignatius would teach that the cross—an image of Christ’s passion, filled with divine power—should be venerated. He expresses this teaching in at least two places in his letters.

Veneration of the Cross of Christ

In his Letter to the Ephesians, Saint Ignatius honors the cross by speaking of wanting to make himself nothing for its sake:

“Let my spirit be counted as nothing for the sake of the cross.” (Schaff and Wade translation)

The Greek word used for “nothing” is often translated “offscouring,” (περίψημα) and is the same word Paul uses in 1 Cor 4:13. Making himself nothing before the cross implies a self-lowering, acknowledging the supreme claim that the cross has on his life and loyalty. An alternative translation is as follows:

“My spirit is a humble sacrifice for the cross, which is a stumbling block to unbelievers, but salvation and eternal life to us.” (Ephes., 18, The Apostolic Fathers, translated by Michael Holmes, 1992)

In this, Ignatius expresses deep devotion and reverence for the cross of Christ, using language that mirrors his sacrificial attitude towards his fellow Christians (Ephes. 8).

We have already noted that for Saint Ignatius, the cross is an inseparable manifestation, sign, and trophy of Jesus’ death. The cross on which Christ suffered—as a physical object, which is an image of Christ’s suffering and death—was therefore venerated by Ignatius.

But Saint Ignatius goes further. In another letter, he speaks of the cross of Christ as imaged and visible to Christians, treated as an object of devotion which is gathered around in the community. In the opening of his Epistle to the Smyrneans (Section I) St. Ignatius discourses on the cross as follows:

“I Glorify God, even Jesus Christ, who has given you such wisdom. For I have observed that ye are perfected in an immoveable faith, as if ye were nailed to the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, both in the flesh and in the spirit, and are established in love through the blood of Christ, being fully persuaded with respect to our Lord, that He was truly of the seed of David according to the flesh and the Son of God according to the will and power of God; that He was truly born of a virgin, was baptized by John, in order that all righteousness might be fulfilled by Him; and was truly, under Pontius Pilate and Herod the tetrarch, nailed [to the cross] for us in His flesh. Of this fruit we are by His divinely-blessed passion, that He might set up a standard for all ages, through His resurrection, to all His holy and faithful [followers], whether among Jews or Gentiles, in the one body of His Church.” (The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, translated by Schaff and Wade)

Here, Ignatius again echoes his teaching that the cross is tree of life ("of this fruit we are by His divinely-blessed passion"). This shows that for this passage, the cross is in view here as an object distinct from Christ’s death.

The Saint continues to develop this teaching on the cross, describing how Christ “set up a standard for all ages, through His resurrection.” To understand what's being said about the cross, we should examine the three phrases: "set up", "standard", "for all ages".

The word for standard is sýssimon (σύσσημον) and is distinctively military language. It is connected in meaning to “sign”, but goes far beyond the concept of a sign communicated by one individual to another, and entails a kind of public, corporately-understood meaning. Niko Huttenen places this outside the category of typical Christian metaphor as internalizing and spiritualizing the meaning of military terms (“put on the whole armor of God”, etc.) which is common in the New Testament and early Fathers. He instead states straightforwardly, "Ignatius of Antioch says that Christ lifted up a “standard” or a “flag” (σύσσηµον) (Ign. Smyrn. 1.2)". (Early Christians Adapting to the Roman Empire, Chapter 4)

Additionally, we can note the language of “raise up” (ἵνα ἄρῃ) is used in Matthew 27:32: “And as they came out, they found a man of Cyrene, Simon by name: him they compelled to bear his cross.” (ἠγγάρευσαν ἵνα ἄρῃ τὸν σταυρὸν) This makes the connection to the cross even clearer, and emphasizes the physicality of what is being described (already implicit in the language of “standard”). The lifting up is “for all ages”, suggesting an object of remembrance that has permanent visibility. This is all best explained if Saint Ignatius is referring to the physical image of the cross as crafted by Christians to represent the true cross.

Standards are inherently objects of veneration. They are honored by being placed high up (exalted), which is an act of a community placing priority on the ideal represented by the standard. By being elevated, the standard can play a unifying role as an object of focus for a mass of people. The standard is always treated with some kind of visible reverence—gathering around it, following it in a procession, etc.—which mirrors commitment to the person, nation, deity, idea, etc. represented by it. Even if it only serves as an object of attention and focus for those standing around, it is still being honored by this physical act.

For Saint Ignatius, the exaltation (honor) given to the standard of the cross (image) passes to the true cross of Christ (prototype)

Given Ignatius' own emphasis upon loyalty to the cross, offering himself to the cross, and honoring it by lowering himself and making himself nothing, we have here a reference to public, ritual veneration of the cross which involved raising it up (and possibly lowering oneself at the same time—bowing). For Saint Ignatius, the exaltation (honor) given to the standard of the cross (image) passes to the true cross of Christ (prototype)

The word standard (σύσσημον) is used in both the Greek Old Testament and in Roman military contexts that make the fact that this involves corporate, public veneration of an image of the cross even clearer. In a future post I will explore these connections. But for now, it is important to note how easy it is to pass by this reference to veneration of an image when reading Saint Ignatius. Just as calling something a “holy icon” today automatically connotes that something is an object of veneration, so also calling something a “standard” in an ancient Roman context entails the same. But it is easy to miss if one is alien to a cultural context which easily recognizes how nature and culture are meaning-laden and glory-bearing.

There was no iconography (i.e. image veneration) by any Christian before AD 500.

You assume that by speaking of "the cross", Ignatius is speaking of an image of the cross rather than the cross Christ died on.

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/article/answering-eastern-orthodox-apologists-regarding-icons/