This post continues to build the case that some Ante-Nicene Christian images of the Good Shepherd were used ritually and venerated by early Christians. In the first post, I argued that the presence of this image in the vaults of the Catacombs and the Baptistry of Dura Europas constitutes it as a genuine holy image (icon) as opposed to a mere decoration, etc.

This post will provide three lines of argumentation that argue that this image was venerated: based on architectural comparanda, the context of the images, and their formal qualities. Scholarly support for many of the central claims in my case is significant, even though the language of “veneration” is not always used to describe the action of Christians towards the Good Shepherd images. All of these lines of evidence coalesce to support a central claim: that in some cases, the pre-Nicene Good Shepherd image was holy to early Christians—and therefore venerated—in a way that is similar to how the image of Christ Pantocrator would later become so important in the Orthodox Church.

Veneration And Comparanda: Architectural Considerations

We have noted how the close connection between tomb, baptism, underworld, and salvation resonates perfectly with the 23rd Psalm, Christ’s self-identification as Good Shepherd, and His Parable of the Lost Sheep. This brings us back to the idea that the Good Shepherd image is meant to manifest divine presence invading the underworld. Already, such an understanding suggests that such an image would have a devotional function, serving as a focal point and inviting prayer to the actual Good Shepherd for salvation.

This is further reinforced by the image’s context above the baptistry in Dura Europas, and its placement in the arcisoleum of the catacombs. It is widely acknowledged that an image’s position in an architectural context can be geared towards evoking a devotional use. If an image follows the same form as various comparanda (artifacts or material remains that it resembles) whose purpose and use is known, this will allow us to draw conclusions about how the image under consideration would have been used. Beat Brenk has argued that in the Roman context, if images of holy things or divine beings are placed high up in a ceiling or an arched vault, they naturally invite an attitude of veneration:

“Mosaics and frescoes in the apses of cult rooms generated very particular effects, evoking in the viewer respect, admiration, awe and maybe even veneration.” (The Apse, The Image, And The Icon pg 109-110)

Brenk reinforces this later when talking about cult rooms in Churches. These developed out of this Roman context to naturally and distinctly lead participants towards veneration, eventually developing towards the image of Christ and the Theotokos so familiar in the central apse of most Orthodox Churches today:

“The Church sat back and watched how mosaics and frescoes in apses of cult rooms generated very particular effects, evoking in the viewer what I propose to call in this book ‘visual worship’. The Virigin with the Child for example, being in full view of the believers, became the focal point of this visual worship.”

Brenk’s comments concern a broad relationship between Roman architecture and Christian architecture that applies in the case of the semi-domed structures (arcisoleum) of the Roman catacombs. However, scholars commenting on the specific worship spaces at Dura Europas have noted how the structures in these places visually evoke ritual engagement. Sean Burrus, in his lecture “Jewish Art at Rome, Beit Shearim, and Dura Europas” applies this principle about how spaces are designed to facilitate devotion to the synagogue at Dura Europas. He highlights the Torah scroll room, which mirrors the image of the Jerusalem temple in the arch above it, surrounded by Jewish liturgical objects such as the lulav, etrog, and shofar:

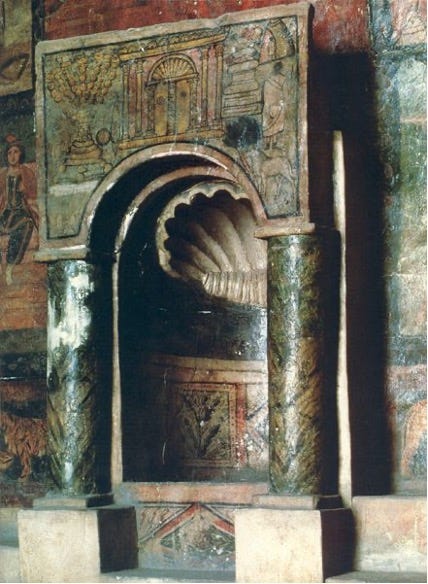

“The Torah shrine was the focal point of the hall, both spatially and visually. It was not only axially aligned with the entrance to the assembly hall, but it also held the scrolls of the Hebrew Bible, the Torah, during liturgies; and so because of that, it was a focal point of worship services and prayer. Architecturally, the Torah shrine featured a raised niche, set between two engaged columns, surmounted by a molded stucco conch. The major portion of the Torah shrine… was painted with panels of solid colors and geometric bands that mimicked polychrome marbles, and the face of the shrine above the niche is really where our attention is drawn. There, predominantly displayed against a blue field, is a frontal depiction of the Jerusalem temple with a rich golden yellow… [which contains] a central feature that has been alternatively identified as the temple doors or the ark of the covenant…”

Burrus’ point that the raised niche with dome-like structure, jutting outward, and supported by two columns is key for facilitating devotion through the enclosed image can be applied further. The same kind of niche structure is present in the Mithraeum at Dura Europas, and also the baptistry in the Christian Church. As one lecturer notes:

"The devotional focus for this [Mithraic] structure is a relief in a sacred niche, for the focus of worship, showing him slaying a bull... images of the deity and his actions are the focus of this structure... [when we consider the synagogue,] the Torah niche on the wall, [is] the focal point of the room as indicated by columns and projection of the niche into space. This is where sacred Scripture would be kept, and makes the focus of devotion for this space the word of God… [In all three spaces, architectural elements] designate what is most sacred in their structures of worship using a niche, a recessed area, separated from the main space using similar visual cues, such as arches or columns, and decorated with imagery. The artists who decorated these structures, all of them—Christian, Jewish, Mithras worshippers, and Baal—were probably the same. They used the same style and similar materials to decorate these holy spaces... in a roman way, the style of art endemic to this town." [From Lesson 3 1 Art and Religion in the Late Antique World Basic Small WEB MBL H264 400; lecturer is not identified]

Thus, the use of known Roman architectural motifs in both the arcisolea of the Roman Catacombs and the lunette over the baptistry of Dura Europas is designed to facilitate focus and devotion through the Good Shepherd image to Christ Himself.

Veneration and Context: Salvation Orants and Prayer Practices

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.