One of the earliest surviving images of the Theotokos and Christ Child is in the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome. The painting features a prophet, star, Mary, and Jesus. While at first appearing to simply be narrative art which references a biblical event, there are a number of features which point to this image being an open-ended or “three-dimensionally participatory” image which is meant to be interacted with ritually and venerated.

In what follows, I will first highlight noteworthy features of the image, building on the work of Catacombs scholar Fabrizio Bisconti. Then I will incorporate insights from my previous section on Roman ritual art to give arguments that the image in question was designed to be venerated.

The 3rd Century Painting of the Theotokos and Child in the Catacombs of Priscilla

The scholar of the Roman catacombs, Fabrizio Bisconti, notes that Catacomb art in Rome tends to be according to the “Second Pompeiian/Roman Style” of painting, which connects it to the wall art in Pompeii’s Villa of the Mysteries:

During the third century, the catacombs were decorated with a type of fresco characterized by this figurative typology, somewhat inappropriately defined as “red and green line style,” which originates in the final synthesis of the Second Pompeian style and simultaneously appears in domestic buildings, especially those of Rome and Ostia, as the decoration of the Villa Piccola of San Sebastiano shows (Ferri 2015). This decorative typology evolves over time in the second half of the third century or throughout the following century. The lines become wider bands, and we see the introduction, especially on the socles and in the negative architecture, of faux marble and transennae (Bisconti 2006a).

(Bisconti, “The Art of the Catacombs”, in The Oxford Handbooks of Early Christian Archaeology edited by W.R. Caraher, T. W. Davis, D. K. Pettegrew.)

Bisconti contextualizes this pre-Nicene (late 200s) image of Mary in the Catacomb of Priscilla as follows:

By the fourth decade of the third century, the paintings of the Roman catacombs begin to embrace scenes related to the infancy of the Savior. The fresco of the Madonna of Priscilla is emblematic, as it is represented in the central area of the first floor of the catacomb. Here appears a representation of a veiled Mary seated with the baby in her arms. In front of her, a prophet in a tunic and pallium points to a star, resulting in a figurative reduction that condenses the prophecy of Balaam or Isaiah, and the fulfillment of the same by the birth of the Messiah. This refined iconographic selection, which alludes on the one hand to the mystery of the incarnation and on the other to the harmony of the Old and New Testaments, marks a response to the Christological controversies that arose in the third century and evolved in complex ways in the fourth-century Trinitarian debates and the disruptive Arian controversy. (Ibid.)

Bisconti’s characterization of this image of Mary and Christ shows a strong connection to later portrayals of Theotokos and Child, even in terms of the appearance of Mary (veiled, seated). It is interesting also to consider the way in which Mary is portrayed as encompassing and surrounding Christ. This can be seen as connected to the broader theme in portrayals of Mary as place of manifestation or place of life: the temple, the throne, the paradise of God.

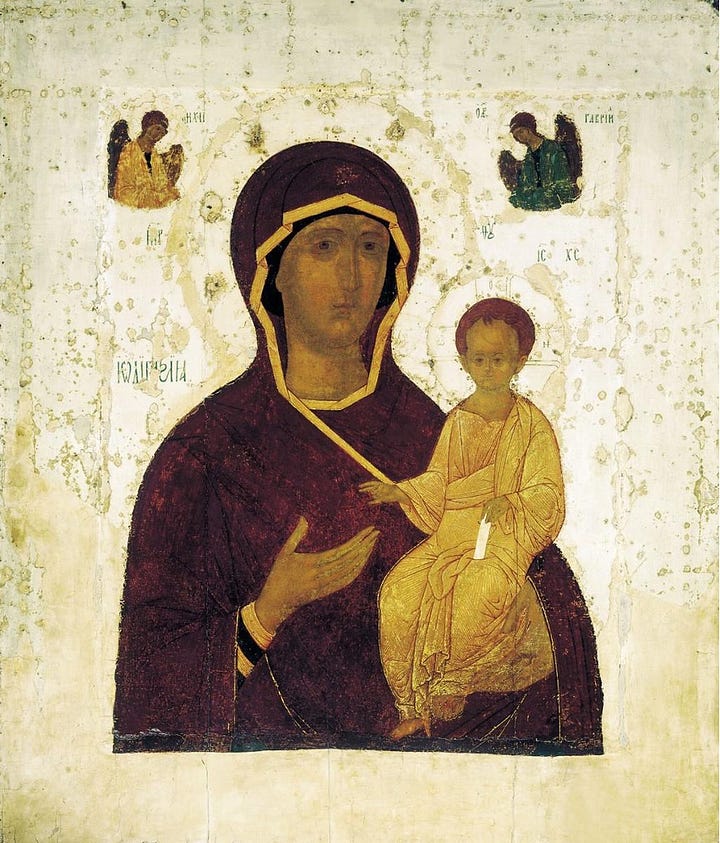

Further, we can note that Christ is facing outwards towards the viewer. This adds an additional element to how Mary is being portrayed: she is showing Christ to us. This is not quite visually identical, but connected in purpose to her portrayal in the “Directress” (Hodegetria) Icon:

It is striking that such an early image of Mary in Rome would be in a pattern similar to this, for the Directress is the form of image attributed to the hand of Saint Luke the Evangelist. While this harmony is not a proof of anything, it is exactly the kind of thing we would expect if the tradition about Luke as the first Iconographer were authentic.

Bisconti notes that parallel images representing the Vistation of the Magi were present in the Catacombs at an earlier date:

Other New Testament episodes related to Christological matters also appear in the third century. A cubiculum of the Catacomb of Priscilla depicts the first scene of annunciation (Mazzei, 1999), and the first adoration of the Magi appears in the Greek chapel, also datable to the middle years of the third century (Recio Veganzones 1980). In both examples, the scenes have a Christological character in the sense that the Madonna is not the true protagonist of the scene but appears as a functional figure in the description of the infantia Salvatoris, a long-running theme that will find its most solemn and complex application in the Sistine arch of the Roman basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, where the canonical scenes that arose in the art of the catacombs are enhanced by episodes inspired by the apocryphal writings, especially by the Proto-Evangelium of James and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew. (Ibid.)

These considerations suggest that by the time the image in the Catacombs of Priscilla under consideration was made, there was already an existing artistic association between the Theotokos and Child on the one hand, and the visitation of the magi on the other. The fact that this precedent existed in Rome beforehand (“middle years of the third century”) increases the probability that this connection was intended by the painter who made this image in the fourth quarter of the third century. As we approach the question of the use of this image, it will be important to keep in our minds the fact that portrayals of the visitation of the magi are plausibly part of the artistic-theological background for this painting.

Arguments That The Image Was Venerated

With the components, qualities, meaning, and background of the image in mind, we now turn to the question of its use. Several considerations support the claim that it was venerated (interacted with ritually in a way that involved honorific attitudes and gestures):

First, as Bisconti notes, the Catacomb art in general follows the Second Pompeiian Style. This is the same style employed in the interactive ritual images from the Villa of the Mysteries. While it is possible to have images in this style which are not designed for ritual interaction, the fact that some paradigmatic and important surviving Second Style art had a ritual function does lay a foundation for the plausibility of the claim that other such images were interactive. The significance of this point is compounded if there are other features which the Catacomb painting has which find comparanda in the highly-interactive art from the Villa of the Mysteries. And it turns out that this is indeed the case, as we shall see in what follows.

A second argument is the use of various formal qualities of an image as a way of directing attention within the image itself. In considering the art which was used for initiation into the cult of Dionysius, it was noted that certain gestures and facial expressions directed towards persons and objects would cue attention to specific parts of the painting and therefore the rituals it represented. When we turn to the image of the Theotokos and Child in the Catacombs, a similar internal logic of attention seems to be present. The fact that the prophet (whether Balaam or Isaiah) is pointing towards the star invites or cues a centering of attention on it. The star itself then becomes a means for directing attention towards Christ. This is present in the symbolic logic of the image already, since stars are signs of light which themselves point to some further referent (a wish, a neverland, etc.). But for the typical viewer who knows the biblical references which are being worked with, the need to re-center attention on Christ and His Mother is even more evident. And Mary looks at her child, providing us a model of attentiveness to the Word of God. Our focus naturally shifts as we look anywhere at the image, becoming re-directed towards the One most deserving of attention.

Third, as we reflect on the scene from the Scriptures which forms the narrative background for this image—namely the visitation of the magi, led by the star to Christ—we come to an important realization. The magi are conspicuously absent. But why would this be the case?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.